RSPCA staff have been looking back at the role they played in helping to save thousands of seabirds across Pembrokeshire - as part of the massive rescue operation following the Sea Empress disaster - which at the time was one of the largest oil spills in the world.

Early on the evening of February 15, 1996 the Sea Empress, a single hull oil tanker, hit rocks on its way into the Cleddau Estuary and the ship's cargo of 130,000 tonnes of crude North Sea oil started to spill into the waters off Pembrokeshire.

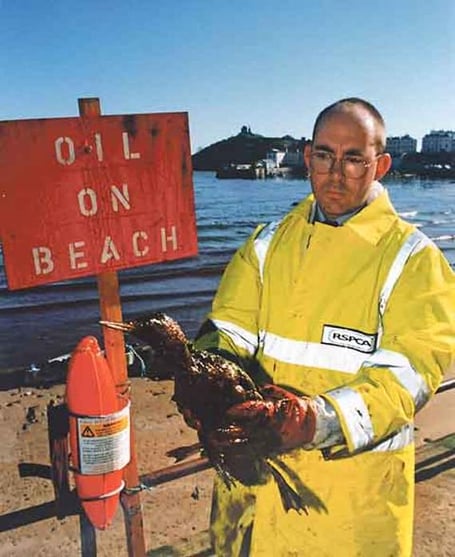

The RSPCA launched a massive rescue operation in response to the disaster in an effort to save the thousands of oiled and dying seabirds that were so badly affected by the slick.

Scores of volunteers helped open and run a makeshift animal hospital - set up in an old industrial unit in Milford Haven - where the sea birds were taken - while 53 RSPCA Inspectors, 14 ambulance drivers and wildlife centre staff experts worked around the clock to nurse, clean and feed as many of the birds back to health as they could.

At the height of the intake almost 760 birds were taken in one day.

By March 5 (1996) it was reported that the oiled bird count was that 2,542 birds had been found dead, 3,142 had been rescued by the RSPCA, and 757 had died in care - with many others taken in by other bird hospitals and others dying at sea.

A group of RSPCA long-serving staff - who were involved in the operation 30 years ago, have been looking back at the massive rescue effort.

RSPCA Chief Inspectorate Officer Steve Bennett has also recognised the dedication of their work on the frontline for turning “a scene of unnecessary loss of life” into a story of hope and recovery.

Richard Abbott, was one of the Inspectors on duty the night the Sea Empress ran aground. He said:“I recall speaking to a Brecon RCC (Brecon Regional Control Centre) tasker who said they had received a call saying a tanker had run aground at Milford Haven and was leaking 30,000 gallons of oil.

“I asked the tasker to ring the Coastguard to double check as I was driving and enroute to an emergency at the time, about 10.30pm.

“She rang me back about five minutes later and said to my astonishment that the Coastguard had confirmed the report. I pulled over and rang the Chief Inspector Romain de Kerckhove at home and started the response.”

Richard recalled the initial “chaos” and how he was tasked to attend the control room at Milford Haven the following morning: “I went down and immediately got thrown into a room with all of these executives from different organisations from all over the UK. But initially nothing much happened.

“We were just kind of getting ready to see where the oil would go because we didn't know where it would land.

“We knew it was out there, but we didn't know if it was going to come down the estuary or not and then we could see it starting to move down when the tide was coming in.”

Romain de Kerckhove, who has been with the RSPCA for 39 years, and is still currently serving as Chief Inspector for Mid and West Wales, said when the tragedy happened organisations were looking towards the RSPCA for direction.

It then fell to Romain to explain to the many organisations, groups and volunteers what needed to be done and to implement a rescue plan.

“We started putting a plan together to send people down to beaches and give them some direction,” said Romain.

“Then after a while it didn't take long before birds started getting picked up and coming in. But by that stage we're only just setting up the makeshift hospital at Thornton Industrial Estate.”

Romain recalled that the press put out that they needed volunteers and “dozens and dozens - if not hundreds turned up” which was initially tricky to manage.

“We found different beaches where we thought the birds were going to come in,” he said.

“Everyone was so well meaning, but if there was one bird located, there were like 50 people all charging down the beach trying to be first there.

“So what we did was the RSPCA Inspectors would each be in charge of a beach and they would have a collection of cardboard boxes and not much else. There they managed the volunteers and organised the efforts.”

Richard added: “Our transit vans were emptied out and those vans would go to the beaches collecting up the boxes of birds - which were mostly common scoters - and then we brought them back up to Thornton Industrial Estate in Milford Haven where we dropped them off and then went back.

“We also had people going out in boats as well. It was chaos initially but things did just click into place and everyone got on with what they needed to do.”

RSPCA branches - also played their part by scanning the beaches - including those in the Gower - for oiled birds and launched an appeal for items to help with the washing of the birds.

“We used towels, washing up liquid, and we needed toothbrushes to wash the beaks,” said Romain.

“After that went on the news, car loads full of this stuff would turn up. Every day I'd be opening the mail at the industrial unit and there'd be jiffy bags full of used toothbrushes.

“And then Procter & Gamble got in touch and before we knew it, we had mountains of Fairy Liquid. We probably needed 200 toothbrushes but we ended up with about 10,000 toothbrushes. So it was a bit chaotic - however, it did show the kindness and generosity of the general public who wanted to help and we were very grateful for the support.”

Richard Thompson, Wildlife Rehabilitation Team Manager at Mallydams Wildlife Centre, also recalls the massive volunteer effort.

He along with Richard Seddon - now RSPCA’s Learning And Development Manager - were both tasked to attend Milford Haven and also recall their roles and response by the RSPCA.

Richard Seddon, who also recalls a visit from Tony Blair on St David’s Day, said: “I didn't arrive till the second week and I can then remember somewhere getting some coloured rings and putting them on the birds when they came in each day. So, at least we knew how long they'd been in there for.”

He also remembers going out with the RNLI to look for birds around the nearby islands off Tenby.

“I got asked for a favour if I could go to Tenby and be picked up by the lifeboat to go out and look and see whether any puffins were coming in as there was still oil so there were concerns about any secondary birds coming in.

“Never did I think when joining the RSPCA I’d be picked up by a lifeboat to go and look for birds. There were just so many organisations involved helping - that was really memorable.”

Neil Tysall (an Inspector at the time) who is currently an RSPCA Intelligence Officer, remembers when he was given the call to attend Milford Haven:“I got a call from my then Regional Manager on a Sunday afternoon asking if I could get myself over to Milford Haven as soon as possible.

“He could not tell me how long I would be away for, but to go prepared for at least a week or two. Accommodation was being sorted locally and I with two others shared a room in a B&B into which the landlady had somehow managed to cram in three single beds.

“I quickly realised I was going to get to know my two colleagues really well and in very short order!

“As it happens very little time was spent there as I spent many evenings providing overnight cover in the holding unit with the oiled birds that were awaiting cleaning.”

Neil said during the day they were patrolling the beaches to collect oiled birds and relayed them back to the holding unit.

“Those birds we found alive were literally caked in oil and sand, in their eyes, up their nostrils and in their beaks,” he said.

.jpeg?trim=7,0,7,0&width=752&height=501&crop=752:501)

“The birds had also doubled in weight, making you realise the enormous effort that each of their movements must take.

“As the days went on fewer live birds were being found and some days it felt like you just collected bodies. Everything was covered in oil.

“My Hi-Vis jacket always bore the scars of the Sea Empress and no matter how many washes, always smelt slightly of crude oil for years to come. What I would have given for my jacket to have been the worst casualty rather than all that unnecessary loss of life.”

Most of the birds - around 90% - were common scoters but the rescuers also dealt with guillemots, divers, gulls and swans.

Romain said: “I think if I remember rightly, our initial plan was just to sort of hold them for a minimal period and then get them to the wildlife hospitals for all of the full cleaning and rehabilitation.

“But then as the days went on, it became apparent that all the wildlife hospitals were completely inundated and we had to find we had to set something else up at short notice. So that’s when we said we need more pools because once we've initially cleaned them we put them in smaller pools and then bigger pools, and we need them there for a week or two before we could test whether we could put them back out at sea.”

Richard Abbott said: “We were putting them in the pools after they had been dried and to make sure that they were waterproof essentially. We'd have officers on duty all night checking those birds because they were in danger of drowning.

“Even though they had little islands to escape onto in the pools, if they couldn't get on there, they would drown because even though they look like they've been washed really well, if there's any oil, they still get water logged.”

The birds were kept in the care of the RSPCA for about two to three weeks and once fit and well they were released.

But there were also difficulties releasing the birds.

“It took some time as the weather was pretty bad,” recalled Richard Thompson. “There was also still some oil that hadn’t been cleaned up, so we had to go much further up north Wales to release them off the coast of Borth.”

RSPCA Chief Inspectorate Officer Steve Bennett said he wished to honour the long-standing staff members who were on the frontline back in 1996, highlight the “incredible collaboration” from other organisations at the time and to note its legacy.

“As we mark the 30th anniversary of the Sea Empress disaster, I find myself looking back with a profound sense of pride and humility,” he said.

“On February 15, 1996, our coastline faced an unprecedented ecological threat. When 130,000 tonnes of crude oil began to spill into the Pembrokeshire waters, it didn't just create a slick on the surface; it threatened the very existence of thousands of seabirds.

“What followed was one of the most magnificent rescue operations in the history of the RSPCA.

“Whether you were patrolling the beaches in the dark of night, coordinating chaos in the Milford Haven control room, or spending 14-hour shifts washing oil from delicate feathers with toothbrushes and Fairy Liquid, your commitment saved lives,” said CIO Bennett.

“This operation was far too large for any one entity to handle alone. The recovery of the 3,142 birds rescued was a testament to the incredible collaboration between organisations and we saw a seamless integration of efforts from many partners.

“To everyone involved - those still wearing the uniform and those who joined us for a few weeks in 1996 - thank you. You turned a scene of ‘unnecessary loss of life’ into a story of hope and recovery.”

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.